How an Underwater Volcano Caused 85,000 Earthquakes in Antarctica in FOUR MONTHS | Unveiled

advertisement

VOICE OVER: Callum Janes

WRITTEN BY: Dylan Musselman

Why was there a major earthquake swarm in Antarctica?? Join us... and find out!

In this video, Unveiled takes a closer look at a bizarre and unexpected series of events on Earth's southernmost continent; Antarctica! According to a 2022 report, there were THOUSANDS of Earthquakes there in late 2020... and scientists are only now beginning to understand why!

In this video, Unveiled takes a closer look at a bizarre and unexpected series of events on Earth's southernmost continent; Antarctica! According to a 2022 report, there were THOUSANDS of Earthquakes there in late 2020... and scientists are only now beginning to understand why!

How an Underwater Volcano Caused 85,000 Earthquakes in Antarctica in FOUR MONTHS

Sometimes, after an earthquake has passed, the ground will shake again in an aftershock. Similarly, if a smaller earthquake precedes a bigger one, it’s called a foreshock. So, between foreshocks, earthquakes, and aftershocks, it can sometimes be that one single disaster unfolds in many parts. But, on top of this, there’s also another, separate phenomenon wherein clusters of full earthquakes are set of one after another, after another. And scientists recently (and unexpectedly) experienced this in one of our planet’s most unique settings: Antarctica.

This is Unveiled, and today we’re exploring how an underwater volcano caused 85,000 earthquakes in Antarctica in four months.

We know that Earthquakes are one of the most destructive forces of nature on this planet. But, often, it’s not the event itself, the actual shaking of the ground, that’s so lethal. Rather, it’s the effects that that shaking causes. Violent vibrations in the earth can uproot and destroy the infrastructure on top of it, and we’ve unfortunately seen many a city reduced to rubble following a quake. Many related deaths come, then, via falling debris raining down onto the ground. Or else, death comes from the secondary disasters that follow earthquakes, such as mudslides or tsunamis. And, while the really big ones thankfully don’t happen every day of the week, earthquakes aren’t rare. In any given year, around 500,000 of them are detected on average, according to US government statistics… although the spread isn’t even. Most of them (about ninety percent) occur around the infamous Pacific Ocean region called the Ring of Fire, an area reaching from far east Asia and Australasia to the west coast of North and South America. It perhaps came as something of a shock to scientists, then, when they recorded 85,000 earthquakes over just a few months in, of all places, Antarctica.

Details of the “massive earthquake swarm” were published in an April 2022 report, in the journal “Communications: Earth and Environment”. In August 2020, an international team of researchers at a station on King George Island, close to the Antarctic coast, caught wind of the first quake. That event in itself was somewhat surprising, but the Earth moves in mysterious ways (literally in this case) and the team might’ve reasonably assumed it to be a one off. But then another one came, and then another… and, well, from that point on the earthquakes just kept coming. On King George Island, an incredibly remote location, the team were reportedly hard-pressed for the facilities needed to measure seismic activity, but they managed to pool data from various sources that were picking these things up. And, ultimately, they started measuring the Antarctic quakes in August (following the first one) and the unprecedented shaking didn’t calm down until November of the same year. They recorded a near continuous stream of earthquakes for around four months, and still more (at a reduced rate) in the weeks that followed… and by the end, they really had measured around 85,000 in total. The majority of them were minor, but there were some larger ones registered, too, including a 5.9 magnitude quake in early October and a 6.0 toward the end of the swarm, in November. For reference, those quakes will have packed the energy equivalent of around ten thousand tons of dynamite. And there were long term effects from some of the shaking, too, with it found that the island on which the team was based had actually been displaced by around four inches. The ground had literally been reshaped beneath their feet, if only by a small amount. All in, big or small, the four-month run now stands as the longest and most powerful seismic activity in Antarctica in recorded history. So the King George Island team (and many others from around the world) were left with one simple question; how did it happen?

Often, earthquakes are plainly the result of tectonic plate activity. When two plates meet, deep in the earth, they rub against, pull away, or push above and below each other… which generates a lot of pent-up energy. As Earth is tectonically active, the plates are always on the move and sometimes, inevitably, they slip… at which point that pent up energy is released, powerful waves rush through the ground, the ground shakes, and an earthquake takes hold. It’s why so many earthquakes happen along the Ring of Fire, because there are so many meeting points between tectonic plates there. But it’s thought that this more typical process isn’t what caused the 85,000 earthquakes in Antarctica.

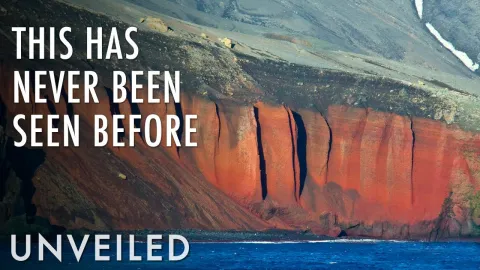

Here, while we are still dealing with a plate boundary - along the edge of the Antarctic Plate, in a region known as the Bransfield Strait - it’s less about the plates pushing, pulling, or rubbing against each other directly. What’s more important are the cracks and fissures that have formed along the strait (over thousands of years) thanks to tectonic instability. So much so that nowadays it’s a reasonably unknown realm of underwater volcanoes down there. These mountainous, submarine features aren’t quite so world famous as some of their on-land counterparts, but they’re no less powerful.

The team on King George Island found that one particular volcano – called the Orca Seamount – seemed to be the most likely cause of their sudden rush of quake activity. This was strange from the outset, though, as the Orca Seamount had previously been listed as inactive… meaning it hadn’t erupted recently and was deemed unlikely to blow in the here-and-now. But logically it must have erupted, or something must at least have happened to it, if 85,000 earthquakes were being traced back in its direction. There followed an investigation into the magma flow beneath and around the volcano, the movements and pressure of which it was found might theoretically have set the earthquakes off – with the magma pressing through the Earth’s crust. The fact that the quakes largely stopped in November poses another problem, though, as it would imply that the pressure was released somehow… again, most likely, via eruption. So, it could be that the Orca Seamount did erupt… but there’s no direct record of that event, and so it’s challenging to prove that that’s what happened. Again, the limited technology available to those on King George Island was reportedly a limiting factor for further study.

So, where do we go from here? We know that 85,000 earthquakes certainly took place; we’re not exactly sure why they happened; but there’s a pretty good theory involving an underwater volcano that had previously been believed to be out of action. One possible course of action would be to send a probe beneath the waves to more closely examine the seafloor around the volcano, to gain a better idea of any eruption event that might’ve taken place. However, at present, there are no plans do so. Nevertheless, the study until this point has been widely celebrated as successful example of what can be achieved even without masses of high-tech gadgetry. Again, the team behind it were hindered throughout by a lack of facilities to measure seismic activity and they were working in an extremely isolated environment… and yet they’ve still managed to paint a picture for the wider world of what’s generally considered to be an incredible unusual Antarctic event. A truly unique and special few months in the history of this icy world.

Clearly, there remain questions left to answer, like; what’s really happening beneath the Orca Seamount? Should a sudden rush of earthquake activity really go down as though it’s an anomaly, or should we now expect to see more events like this in the future? And just exactly what is the Earth trying to tell us when it rumbles for so long at its southernmost point?

In the coming years and decades, research into Antarctica specifically is set to increase. Of all the continents on Earth, it remains by far the least explored, the most hostile, and the most mysterious. But that also means that we have so much left to learn from it. And, really, the uncovering of endless tectonic events is just the latest chapter in the story. Because that’s how an underwater volcano caused 85,000 earthquakes in Antarctica, in four months.