Scientists Just Photographed the Milky Way's Black Hole for the First Time | Unveiled

In this video, Unveiled takes a closer look at the first ever photograph of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of our galaxy! Thanks to a team of scientists at the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration, we can finally confirm what's hiding at the heart of the Milky Way... with one of the most incredible photos ever taken!

Scientists Just Photographed the Milky Way’s Black Hole for the First Time

It’s been widely believed for a long time – by astronomers and scientists – that at the center of our galaxy, the Milky Way, there lies a supermassive black hole. A cosmological colossus around which the whole of the rest of the galaxy orbits. The problem has always been, however, that we’ve never had any direct evidence that a supermassive black hole is definitely what’s there. Instead, it’s always been more a confident assumption. But now, following the release of an incredible photograph, we finally have all the direct evidence we need.

This is Unveiled, and today we’re taking a closer look at the extraordinary, new, and ground-breaking image of the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

If you were to leave Earth, leave the solar system, and travel roughly 25,000 lightyears in the right direction, you’d eventually reach the heart of our galaxy. A mysterious realm that holds the Milky Way together… because the Milky Way doesn’t just move through space at random, but rather it’s gravitationally bound to a giant something called Sagittarius A-star. Until now, Sagittarius A-star had usually, technically been referred to as a massive and compact radio source widely believed to be a black hole. But now we know it certainly is a black hole, because we’ve got the pictures to prove it.

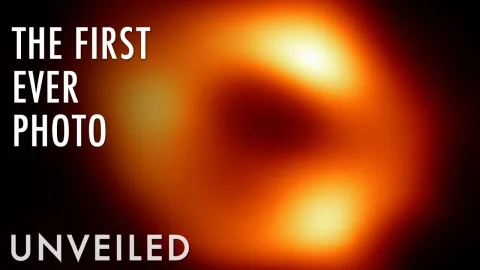

The Event Horizon Telescope (or, EHT) Collaboration published the first ever photographs of Sagittarius A-star on May 12th, 2022. And, if we cast our minds back to April 2019, when the first ever black hole photograph of any kind was published, yes… that feat was also achieved by the team at the Event Horizon Telescope. Back then, it was all eyes on the distant, alien galaxy, Messier 87 (or, M87), as the unassuming, orangey ring of the black hole at its center captured the whole world’s imagination. But now, our attention is firmly fixed on our own house, as the Milky Way takes center stage.

The new photograph was again produced by an array of EHT telescopes, based on observations initially made by them back in 2017. And, again, it shows an orangey blur… but, as indistinct as it might appear on first viewing, this image will surely go down as one of the most significant images in modern scientific history. We see that the orange color again forms a ring around a dark and enigmatic center, the black hole itself. This is essentially the light that’s closest to the black hole, and therefore the light that’s next in line to fall into it. We, of course, know that nothing can escape a black hole. Once anything – even light – passes the event horizon, that’s it. Gone. Plunged into an unknowable realm where the laws of physics literally break apart, and never to be seen again.

Those working at the EHT have stressed that this was by no means an easy photograph to take. While Sagittarius A-star is certainly closer to home than its M87 counterpart, there are still some 25,000 light years between us and it. Sagittarius A-star is also considerably smaller than the M87 black hole – around 1,500 times smaller, in fact – which makes zooming in on it even harder. And then there was lots of space stuff in the way, as well. As is hardly surprising, the long-distance path between us and our galaxy’s core is never clear. There’s always dust, gas, and debris to contend with, all of which can make capturing discernible images impossible. And that’s before we even consider the distortion around the black hole itself, where space and light gradually begins to behave less and less like we’d usually expect it to. In accompanying papers, published in “The Astrophysical Journal Letters”, the astronomer Geoffrey C. Bower (who’s a member of the EHT team) noted the “significant complexity to the imaging”… explaining that in order to produce the picture, “the collaboration employed a number of traditional and novel techniques”. This was a long, long way away from simply lining up the image and pressing the button, then. It took a great deal of planning and execution.

But the effort is certainly worth it, as Bower also refers to the photograph’s supermassive subject as being “the ultimate laboratory for black hole astrophysics”. It’s almost ninety years since the first signals from Sagittarius A-star were first detected. Back then, theories on black holes (in general) were still relatively young, with one Albert Einstein’s ideas informing much of the early research. But, while black holes are now accepted as an integral part of the universe, there’s still so much we don’t know about them. While most of everything else does fit with how we expect reality to be… black holes just don’t. It’s why they’ve become such a favorite point of interest in science fiction media, because the answer to the question “what happens in a black hole?” is still “nobody knows for sure”. The hope is that by directly imaging black holes, we can begin to better understand them. We’ve had a vague idea about their structure, the accretion disk, and their infinite mass but stealthy existence for years now… but it could soon be time for that vagueness to be transformed into cold, hard understanding.

And, what then? In many ways, getting to know the black hole at the heart of the Milky Way isn’t going to change our day-to-day lives all that much. It’s far enough away not to immediately concern us, we’re not about to get pulled into it ourselves… and, really, even if it was a more localized and pressing matter, there’s essentially nothing we could do against the might of a supermassive black hole, anyway. If it were coming for us and we wanted to outrun it, we simply wouldn’t be able to. But, on the other hand, this thing is absolutely integral to our being here, alive, right now. It anchors the sun, which anchors the Earth, which is bound to the moon, which is all part of the majestic balance that ultimately makes human life possible. A supermassive destroyer of literally everything, it can easily feel like quite a frightening prospect… but, if it were to suddenly disappear, then gradually, probably, so would we.

Again, the “halo” in this most recent image could just as well double up as just another hazy and inconsequential smudge in the endless vista of space… but, actually, that halo is light that’s countless generations away from us and it’s literally bending under the weight of the black hole’s influence. The material that flies around Sagittarius A-star, the stuff that makes it possible to even spot it in the first place, is doing so at around the speed of light. The whole thing together contributes a mass to the universe that’s around four million times greater than the sun… which is some going when you consider that the sun accounts for ninety-nine percent of the mass of the entire solar system. This apparent “smudge”, then, is in reality a record of a realm of absolute extremes. There’s no other place like it in the galaxy. But, then again, it’s thought that there are plenty of other places like it in the universe as a whole… seeing as it’s widely believed that supermassive black holes like Sagittarius A-star (and the one in Messier 87) are to be found in most galaxies. And there could be more than two trillion galaxies, in total.

Looking ahead, thankfully it seems unlikely that this is the last we’ll hear from the Event Horizon Telescope. With the first ever photo of a black hole in 2019, and the first ever photo of our galaxy’s black hole in 2022, the project has already contributed two of the most important scientific moments of the twenty-first century. But, with multiple, cutting-edge telescopes stationed all across the world map, with more facilities set to be built, and with a team of more than three hundred dedicated astronomers poring over the data… there’s no doubt more to come.

For now, though, we can enjoy what has reportedly always been the EHT’s primary target, our very own Sagittarius A-star. And we can reflect on the fact that one of our biggest mysteries about space has finally been solved. The next time you look out into the stars, you can now know with certainty that somewhere out there there’s a bottomless, merciless, all-consuming void that’s holding the whole show together. Which is perhaps quite comforting, in its own way. And that’s how scientists have just photographed the Milky Way’s black hole for the first time.