The Evolution of The Simpsons

“The Simpsons” is one of primetime’s most iconic animated shows, if not the most iconic animated show. This game-changing series likely wouldn’t exist, however, had it not been for a last-minute change. When “The Tracey Ullman Show” producer James L. Brooks wanted to incorporate animated shorts, Matt Groening planned to pitch his comic strip “Life in Hell.” At the risk of losing the publication rights though, Groening instead devised another idea about a dysfunctional family shortly before his pitch meeting. Already naming four out of the five characters after his own family members, Groening felt it would be too obvious if he named the eldest son Matt and instead went with Bart, an anagram for “Brat.”

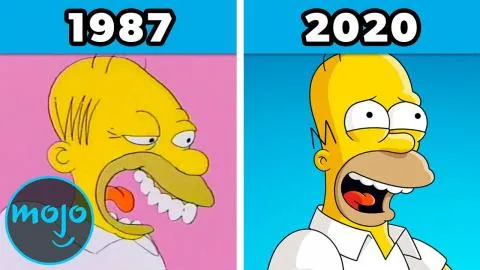

On April 19, 1987, the world was introduced to Bart, Homer, Lisa, Marge, and Maggie in the first “Simpsons” short, “Good Night.” Troy McClure sums it up best. Since the animators just traced over Groening’s sketches, the animation was on the cruder side. Nevertheless, the shorts proved popular and funny enough for Fox to greenlight a half-hour series, which Groening and Brook co-produced alongside Sam Simon. The Christmas special “Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire” aired on December 17, 1989. The pilot was Fox’s second-highest rated broadcast at the time and as the first season got rolling, “Bartmania” took over popular culture. Yet, the show was still finding the look and voice that would define later seasons.

After season two, Groening and Brooks stepped down as showrunners, but remained involved in the series. Simon, having clashed with Groening and Books, left production entirely, although he maintained his executive producers credit and a cut of the show’s profits. Writers Al Jean and Mike Reiss took over as showrunners in season three, which is when “The Simpsons” really came into its own. Not only was the animation a lot more solid, but the characters were more three-dimensional, the parody was sharper, and celebrity guest stars became part of the show’s DNA. It was also during this era that the show’s focus started shifting from Bart to “Captain Wacky,” later renamed Homer.

“The Simpsons” would receive new showrunners every couple of years with each bringing their own unique signature to the table. David Mirkin helmed the show from seasons 5 to 6, during which time the series really started to embrace the animation medium. Mirkin took the Simpsons to places most live-action sitcoms wouldn’t (or couldn’t) venture, such as outer space. As over-the-top as storylines would get, the Mirkin years also delved deeper into the show’s emotional core, as seen in season 6’s “And Maggie Makes Three” and “Lisa’s Wedding.”

Where Mirkin started to put more emphasis on the show’s supporting players, Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein decided to shine the spotlight back on the Simpsons family when they took over in season 7. At the same time, the duo opened the show up to more experimentation, producing out-of-genre episodes like “22 Short Films About Springfield” and “Simpsoncalifragilisticexpiala(Annoyed Grunt)cious.”

Mike Scully was promoted to showrunner in Season 9 and most fans would agree that this marked the end of the golden age. That’s not to say the Scully years are bad. The show remained consistently clever with the episodes “Trash of the Titans,” “Behind the Laughter,” and “HOMR” all winning Creative Arts Emmys. Yet, it was around this time that character development and continuity got thrown out the window. Nowhere was this more apparent than in season 9’s “The Principal and the Pauper.”

Often considered a shark-jumping moment, the episode revealed that Principal Skinner was an imposter, altering his character’s whole history. By the end of the episode, however, everything reverts back to normal, and the town pretends it never happened. While the episode does deliver some big laughs, they come at a great price. Skinner’s voice actor, Harry Shearer, even told the writers, “You're taking something that an audience has built eight years or nine years of investment in and just tossed it in the trash can for no good reason.” This set a precedent for the rest of the series as it became less about character-based jokes and more about out-of-nowhere throwaway gags. And we haven’t even mentioned the elf jockeys yet!

Al Jean returned as showrunner in season 13 and has steered the ship ever since. From this point on, “The Simpsons” has had its ups, such as the 2007 theatrical movie, and its downs, such as season 23’s “Lisa Goes Gaga.” Yet, it never reached the same heights as those early years. Somewhere down the road, the characters started to become one-note caricatures of their former selves, even giving birth to the term “Flanderization.” It’s ironic that a lot of people consider “Family Guy” a “Simpsons” knockoff when modern “Simpsons” episodes are a lot more reliant on the random jokes and pop-culture references we associate with the Griffin family.

To its credit, “The Simpsons” has never looked better. The series made the leap from celluloid animation to digital ink and paint in season 14 and upgraded to high-definition in season 20. The newer episodes have much smoother animation, packing in more visual gags than ever before. Couch gags have also grown more ambitious with guest animators even being brought in. This just goes to show, however, that the creative team has become more interested in producing a string of catchy gags rather than writing a flowing narrative. The Simpsons are now vessels who exist to tell jokes, most of which feel forced and not that funny.

Where other long-running cartoons like “South Park” have at least tried adapting with the times, “The Simpsons” seems stuck in a primordial state. The show is still prevalent in today’s pop culture world, but this is mainly due to our nostalgia for classic episodes and their strange and hilarious ability to predict current events. With the passing of cast members like Marcia Wallace and Russi Taylor in recent years, however, many feel the show needs to finally call it quits. In 2019, theme composer Danny Elfman reportedly claimed that the series was on its way out. Al Jean, however, said that the show isn’t ending and it’s at least renewed until season 32.

Over the years, “The Simpsons” has slowly devolved in terms of humor, character, and story. What “The Simpsons” embedded in our culture, though, is still very much evolving. When the show hit the airwaves in 1989, it revolutionized animation with its adult appeal, political satire, and ingenious parodies. We can see its impact in modern animated shows like “BoJack Horseman,” “Rick and Morty,” and “Bob’s Burgers.” Its influence isn’t restricted to adult animation either, finding its way into shows geared towards younger audiences like “Adventure Time.”

Even Disney, which for years has prided itself on being family-oriented, has adopted some of the show’s edge and wit with movies like “Zootopia” and shows like “Gravity Falls.” This isn't all that surprising, seeing as how a lot of “The Simpsons” alumni went on to work at Disney/Pixar, including “The Incredibles” director Brad Bird and “Wreck-It Ralph” director Rich Moore. So, maybe it’s fitting that “The Simpsons” is on Disney+. We’ll just have to see if “The Simpsons” will ever end or if the franchise will evolve further. For now, though, we still have those golden years, which continue to inspire other animators, and will inspire all TV creators for generations to come.

Sign in

to access this feature